Why You Can Not Enter a New Market Remotely

Drawing on hands-on experience with market entry in the UAE and emerging markets, this article examines why go-to-market strategies often fail when built remotely. It explains the limits of desk research, analytics, and local partners — and why physical presence and direct market exposure are critical to building a workable go-to-market strategy and achieving real traction.

Sergei Andriiashkin

Founder and Strategy Partner

New Markets

/

Jan 26, 2026

Over the past few years, I have worked extensively on market entry and product launch projects across the UAE, Indonesia, Russia, and Kazakhstan. Formally, these contexts were very different: company size, level of maturity, available resources, and industries. What follows are several recurring situations I have encountered in these projects — think of them as a set of practical anti-recommendations.

Most teams genuinely believe that entering a new market is a sequence of correct steps: product, partners, hypotheses, presentations, pilot, team. All of this is indeed necessary. In practice, however, the real difficulties begin much earlier — at the stage of research and, more importantly, at the stage of understanding the market and the customer.

"The Market Can Be Understood Remotely"

The first and most common illusion is that a market can be understood remotely. Desk research, analytics, reports, local agencies, dozens of slide decks. Over the past year, this has been reinforced by deep-research modes in ChatGPT, Claude, Perplexity, and other LLM-based tools. It feels sufficient. Yet fairly quickly it becomes clear that this volume of data does not translate into strong, actionable hypotheses.

Not because the research is poor, but because you do not feel the living fabric of the business: usage scenarios, context, nuances. You are simply outside the world in which your customer actually lives.

We experienced this firsthand when one company was exploring which products could be taken to the Indonesian market. We started with internal desk research, then engaged a strong local research agency that followed our brief, conducted a series of in-depth interviews, analyzed market materials, and delivered several substantial presentations with findings and hypotheses. There was a lot of material. It was expensive and well-produced — and I am not even sure we fully processed all of it. Yet it felt lifeless.

Only after we arrived in Jakarta and began speaking directly with small business owners, market vendors, local entrepreneurs, officials, competitors, and expatriates who had lived and worked in the country for years — buying goods and services in everyday retail — did it become clear which of our hypotheses were even worth discussing. What changed was not the data. What appeared was context.

A related layer of the same problem is language and communication. Even if everyone formally speaks English, that does not mean you can discuss real usage scenarios, needs, and pain points. In the UAE, there are dozens of nationalities and dialects, different cultural codes, business norms, and interpretations of trust and responsibility. In most cases, you will indeed conduct interviews and collect a large volume of information — but rarely will you penetrate deeply.

In Indonesia, corporate English worked only as long as we stayed within a formal business environment. Once we went into the market to speak with vendors and owners of service businesses, communication without a local guide who spoke Indonesian became almost impossible.

In the UAE, this is reinforced by yet another illusion: the belief that a local partner can substitute for your own presence. It is often assumed that a partner can “close” the context gap. In reality, a partner is an amplifier, not a substitute. If you lack your own understanding of the market, a partner will simply amplify your mistakes. They can provide feedback, but they cannot transmit a lived sense of a market you are not personally embedded in.

"We Know the Market Better Than the Customer"

The second illusion, which is rarely articulated directly, is related to expertise. To ask the right questions of a market, you must understand what you are asking about. Even strong research agencies that have delivered dozens of projects often operate outside a deep understanding of your specific product — and training does not solve this problem.

Without that understanding, interpretations of in-depth interviews tend to be either superficial or difficult to apply in practice. This is precisely why founders, product managers, marketers, and sales leaders must participate in research personally, rather than relying on a “finished presentation” from which conclusions are supposedly drawn afterward.

At a minimum, you need someone who understands customers, products, and the industry and can correctly interpret research data and translate it into product or go-to-market strategy. Moreover, when respondents see that you genuinely understand what you are asking about, trust increases dramatically.

There is also a reverse side to this illusion. Teams sometimes believe that their product or technological expertise is so strong that it is not the customer who should explain their business to them, but rather the team that should explain to the customer how to automate processes, implement technologies, and redesign operations.

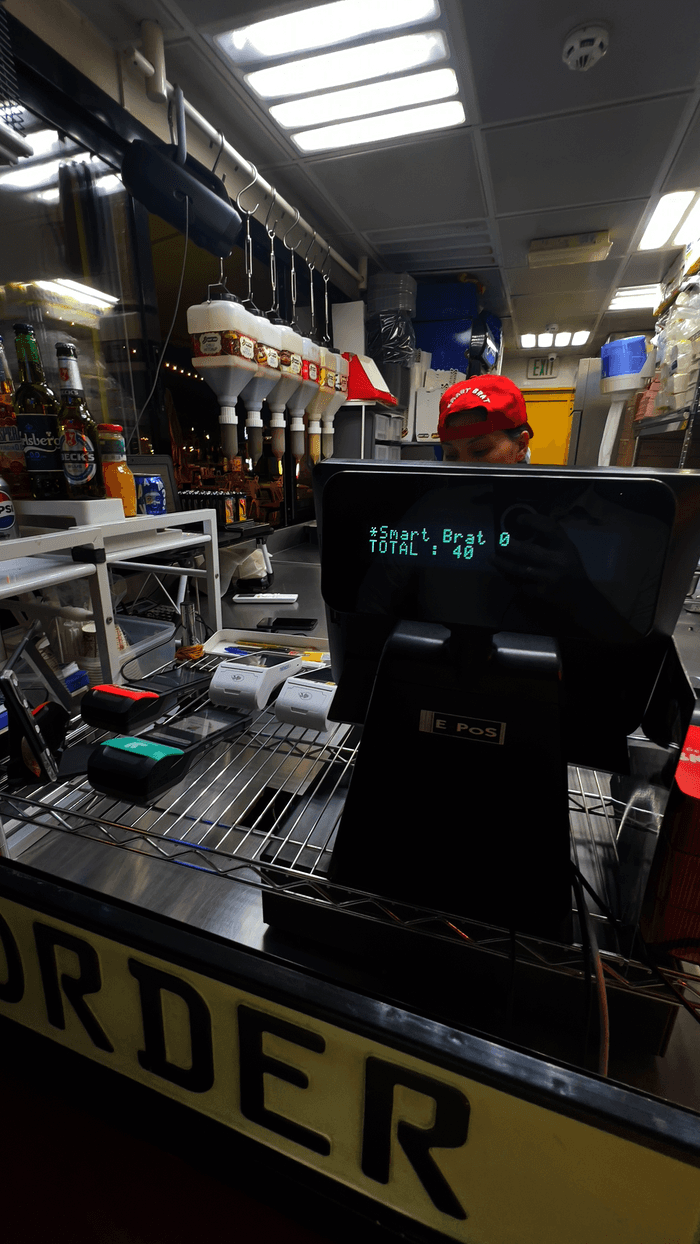

What gets overlooked is a simple fact: the customer has already managed — well or poorly — to build a functioning business without your advice. Once, a customer of Evotor commented under one of our posts: “Thanks for entertaining us, but you don’t fully understand real business.” At Evotor, to truly understand customers’ operational realities, test the product properly, and create genuinely useful content, we eventually had to launch our own coffee business.

"Analytics and Metrics Mean We See the Customer"

The third illusion most often emerges in large, mature organizations: if we have analytics, processes, research, and brand metrics, then we already see the customer.

I experienced this personally when I moved from being an employee of a company to becoming its corporate customer. As long as you use corporate connectivity, corporate scenarios, and corporate logic, many real customer problems simply do not exist within your field of vision and never appear in reports.

Only by stepping out of that position and living as an ordinary user do you begin to see what no metric was capturing. GEMBA walks, fieldwork, involving the entire team — not just sales — in customer interactions, banning the use of your own products in “corporate” mode, and hiring people with a research mindset all contribute to much more accurate and grounded feedback.

Market Entry Is Not Strategy — It Is a Shift in Position

In market entry projects I have worked on, the role almost never starts with strategy. It starts with presence — in the field, in negotiations, in informal conversations, and in decisions that cannot be delegated.

Markets differ. Scales differ. Companies differ. But entering a new market is not about transferring a strategy. It is about rebuilding thinking, roles, and decisions within a real environment. And without physical presence, that rebuilding rarely happens.

This does not mean that entering a new market necessarily requires a large office, a full-scale team, or immediate heavy investment. But it almost always requires a different level of involvement: physical presence of key roles, personal participation in research, conversations outside formal interviews, and decisions based not on reports but on observation.

A minimal “field” phase — before strategy, before branding, before scaling — often saves months and millions at later stages. Most importantly, it allows decisions to be made not from a position of convenience, but from the reality of the market you are actually planning to enter.