How to find, choose, and launch partnerships that truly change a company’s trajectory

A guide for those who want to enter a new market or scale using the strategic partnerships

Sergei Andriiashkin

Founder and Strategy Partner

Strategy

/

Dec 29, 2025

A guide for those who want to enter a new market or scale

In the 2010s, Tele2—one of the first operators in Europe to roll out 3G and 4G networks—hit the limits of its discount business model. Higher CAPEX and low prices don’t naturally go together. The breakthrough came through partnerships with competitors: TeliaSonera and Telenor, each enabling Tele2 to share infrastructure costs and delivery effort.

When the Fortis startup entered the UAE market in 2024, it needed a partner that could provide payments infrastructure (devices and services) and open access to the market. The answer was a strategic alliance with Network International.

Across 25 years of leading and advising business transformation projects—across industries and contexts, with Tele2, Evotor, Fortis, and many others—I’ve repeatedly seen the same pattern: partnerships are almost always at the heart of strategy, yet they are rarely treated as a strategic instrument. Sometimes partners become a growth engine; other times they become an invisible constraint.

This article is a practical guide for founders, strategists, and marketing leaders who work with growth architecture — not just tactics.

Why most people misunderstand “key partners”

In the Business Model Canvas, the “Key Partners” block is often filled in as an afterthought. Once teams complete customer segments, the value proposition, revenue streams and cost structure, and channels, they place everything that didn’t fit elsewhere into Key Partners: contractors, suppliers, advertising channels, useful contacts, “who we already work with,” “who influences us,” and so on. Formally, the box is filled—but strategically, it usually means very little. The issue isn’t the tool; it’s the mindset.

Key partners are not a list of counterparties. They are a structural element of the business model that directly shapes growth limits, market access, and the company’s ability to move forward.

A key partner is

an independent actor who controls a scarce, strategically important resource for your business—capital, know-how, market access, customers, brand, and the like

embedded in the model and makes it possible (or materially more effective).

who can’t be replaced without changing the strategy and the business model itself.

In practice, key partners are usually easy to name explicitly: not “suppliers” in general, but Company X—or X and Y. You can clearly describe the resource they provide and the role they play in your model. They have agency: their own agenda and interests. They are one of the core objects of your attention—and often the first place you see risk and dependency show up in your P&L.

A quick test for your business:

• If this partner disappeared tomorrow, what would break first?

• What resource do they provide that you cannot simply buy with money?

• What can’t you do strategically because of them?

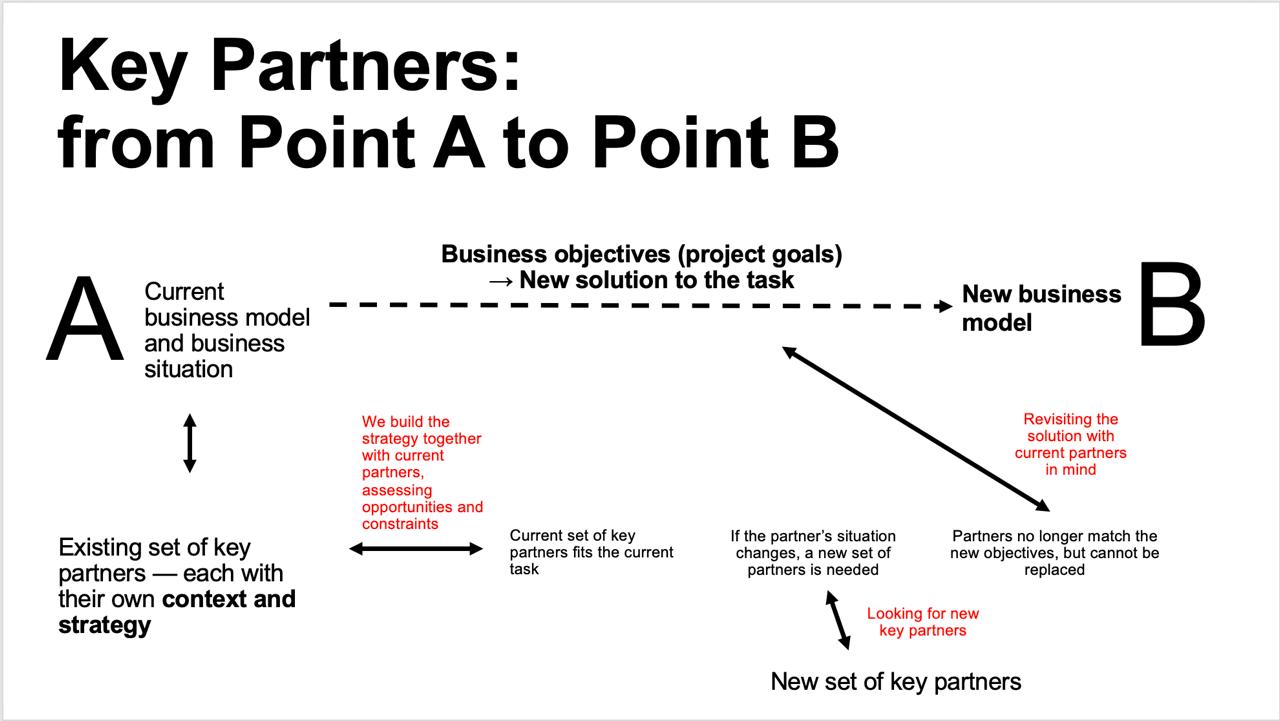

The method: from Point A to Point B

Now imagine you’re building a strategy for entering a new market or launching a new line of business. This is a frequent type of request we work with at Vinden.one—and one of the central themes in my own practice. Where do key partnerships come into that work?

The approach follows a clear sequence: diagnosis → strategic bet → partnership design as a business-model component. This isn’t a conversation “about relationships.” It’s about business configuration.

Step 1. Diagnose Point A: where you are now and what limits you

We don’t start by searching for new partners. We start by understanding the current state. The focus isn’t a list of companies—it’s the boundaries of the current partnership model.

We clarify:

Who actually influences the company’s ability to operate and grow? Why do we consider them key?

Which scarce resources are being secured through partnerships? What is the partner’s real contribution

Where is the critical dependency, and where is the strategic constraint? At this stage there is no “good” or “bad”—only the facts: what the business depends on, and where it hits a ceiling.

How is the work structured today?

Important: at this stage there is no “good” or “bad” judgment. It’s about stating facts: what holds the business at its current point, through whom, and where it hits the ceiling.

Sometimes it becomes clear that the partners sustaining the current model also prevent the move to the next stage.

Example: a consumer goods manufacturer works through a distributor that provides access to retail chains. This works as long as the goal is shelf presence. But when the company wants to shift to direct e-commerce sales, the distributor becomes a constraint: it controls pricing and customer data.

Step 2: Strategic bets—what must change

After diagnosis, the next question is inevitable: if the current configuration limits growth, what transition are we actually trying to make? Here we work with hypotheses of strategic transition—an explicit choice of the future scenario the business is willing to own and be accountable for.

Define Point B:

A new market or segment?

A new business model or revenue stream?

A new stage of development (local → national, Russia-only → international)?

Define the strategic constraint: What exactly prevents us from reaching Point B? What resource do we lack? This could be:

missing technology;

no access to the market/channels;

lack of legitimacy/reputation;

insufficient capital;

regulatory barriers;

missing competencies in the team.

Example: a fintech startup wants to enter the UAE. The strategic constraint is the lack of payment infrastructure and licenses. Building it independently would take years and millions of dollars.

Step 3. Design the partnership using the Partner Strategy Canvas

Now we are ready to design a partnership as an element of the business model. For this I use my own tool — the Partner Strategy Canvas — a structured hypothesis that needs to be tested.

3.1 The scarce resource

Formulate: “We need a partner who provides…”. This could be:

legitimacy/reputation in the market;

technology or infrastructure;

sales or distribution channels;

access to customers/data;

financing;

regulatory capabilities;

competencies.

3.2 The partner’s role

Define the type of partner to know where to look. I use two dimensions: relative to your business and relative to the market.

Relative to your business:

strategic partner (investor/shareholder);

supplier;

customer (including an anchor customer);

competitor;

channel.

Relative to the market:

platform/ecosystem;

gatekeeper (controls access);

anchor customer;

infrastructure player;

anchor brand.

Example: if you need access to a regulated market (fintech, healthcare), look for a gatekeeper — an organization that already has licenses and infrastructure.

3.3 Candidate landscape

Build a named shortlist. Evaluate using criteria such as:

resource availability: do they actually have what we need?

trajectory alignment: where is their business — and the owner — headed?

controllability: how much influence can we realistically have over the partnership?

dependency risk: what happens if the partner abruptly changes terms?

A few years ago, I launched a program for Evotor and its partners called “Growth Trajectory.” Its purpose was to map and align the development trajectories of the market, Evotor, the ecosystem the company was building, and dozens of key partners.

3.4 Value exchange (win-win)

The core of any partnership is mutual benefit. We analyze:

what we need;

what our partner needs;

what we provide;

what the partner provides.

This is not an abstract “win-win” — it is a value exchange that creates gains for each side. Critical point: if you cannot clearly articulate what the partner gets, the partnership won’t take off.

3.5 Risks and constraints

Partnerships are not only about benefits, but also about constraints:

conflict of interest (the partner works with your competitors);

dependency (the partner can dictate terms);

control (the partner gains access to your data/processes);

abandoning part of the strategy (some decisions become impossible).

Important: these risks should be captured upfront and mitigations planned.

3.6 Partnership MVP

Don’t start with a large contract. Define a minimal validation format:

what we are testing;

the first joint activity (pilot/test);

expected outcomes;

success metrics (one or two key ones);

timelines.

MVP example: a joint pilot in one city/segment for 3 months. The primary metric is conversion of the partner’s customers into paying users of our service. Target: 15%.

3.7 Hypothesis check

Final question: why does this partnership enable Point B? If you cannot provide a clear answer, go back to Step 2 or 3.

Step 4. Reflection: what changed

The final step isn’t reporting—it’s locking in a shift in thinking. We return to the starting point and review how our understanding of key partners changed, which dependencies became visible, which partnerships we consciously decided not to pursue, and what new risks emerged.

Three key takeaways

A partnership is not an agreement — it is an element of the business model. A working partnership is embedded in strategy and directly affects the boundaries of growth.

Don’t start by searching for a partner — start by understanding constraints. First diagnose Point A, then define the strategic bet (Point B), and only then design the partnership.

Partnership is always about exchange. If you cannot clearly explain what the partner gets, it’s not a partnership — it’s your wish.

What’s next

Step by step, the Partner Strategy Canvas turns a partnership from a “deal” into an engineered construct embedded in the business model.

In my course at British Higher School of Design and Art, we deliberately go beyond slides: we watch films and discuss books where partnership models are revealed with striking clarity. For example, Guy Ritchie’s The Gentlemen—in a short scene of just a couple of minutes—captures the full logic of key partnerships: who the key partner is for the main character as an entrepreneur, which resources he needs and who controls them, how the value exchange works, and how a deliberately designed partnership is maintained and developed.

A final strategy test: Who is your key partner in reality—and what exactly do they control in your growth? If you’d like, we can unpack this using one concrete example from your business.