The Gentlemen by Guy Ritchie: A Case Study in Partnerships, Status and Exit

If you strip away the cannabis, the crime and Guy Ritchie’s trademark British humour, what remains is a remarkably clean case study in key partnerships as an element of strategy.

Sergei Andriiashkin

Founder and Strategy Partner

Partnerships

/

Jan 23, 2026

For several years now, I have been lecturing on partnerships as part of business models and corporate strategy on the Marketing and Brand Management programme at the British Higher School of Art and Design. Over time, I have collected examples that illustrate different formats and scales of business partnerships. And sometimes the best business cases are not found in Harvard Business Review, but in good cinema.

In The Gentlemen, there is a scene in which Matthew McConaughey’s character explains how his business works (revisit it — roughly minutes 16 to 18). Formally, it is a monologue about an illegal operation. But if you remove the drugs, the crime and the stylised humour, what remains is a rare, almost textbook example of how key partnerships function within a strategic architecture. In class, we watch these two minutes and then analyse them using a framework I developed for the course.

Let’s try to dissect this case together.

Who is the protagonist? What are his personal goals? And what resources does his business require?

The protagonist is Mickey Pearson.

Mickey has a personal goal — and it is not about money (money is merely a tool). He wants to move into a different league: out of the criminal world and into high society. To belong. To live and operate in an environment governed by different rules, a different language and a different social code. Not to hide, not to constantly look over his shoulder, not to feel temporary. It is a deeply human motivation: to change one’s environment and status.

The instrument for achieving this is entirely rational — a successful exit. To sell the business, not as “production” or a set of skills, but as a fully formed system: closed, secure, distributed, resilient to external scrutiny and internal failure. His personal objective and business objective are tightly intertwined, and his approach to partnerships serves both simultaneously.

What unique resources are required — personally and within the business model?

If we separate the levels, the resources differ. For Mickey as an individual, the critical resource is social legitimacy. The ability to exist in the right circles without tension or suspicion. To be perceived as “one of us” in high society and to operate according to a different social logic. This is not directly about money, but it is directly about status, comfort and life after the exit.

For Mickey’s business, the key requirements are security, discretion and reliability as the foundation of the infrastructure — the ability to build production and logistics without external attention or operational disruption. In addition, access to sales channels and networks embedded in a stable, closed ecosystem that does not depend on specific individuals and can be transferred as part of an exit.

Who are his key partners? What resources do they have — and what do they lack?

“All that lot — aristocrats, dukes, duchesses, lords, ladies. Land in abundance. Cash — none. The houses need maintaining, damp needs fixing, silver needs polishing. Remember: cash is the only persuasive argument for aristocrats battered by taxes and politics. Half of any inheritance goes straight to the state.”

Mickey’s key partners are twelve British lords — aristocrats and estate owners. They possess land, status and cultural immunity, coupled with a complete lack of interest in operational involvement. They own significant assets but suffer from chronic cash shortages: estates must be maintained, bills paid and family skeletons kept firmly in the cupboard.

In the film, the aristocracy is portrayed in an almost grotesque way — as a decaying, helpless class. This exposes an additional need: problem-solving. For some, it is repairing a roof; for others, dealing with drug-addicted children. And these are not problems that can always be resolved through formal channels.

What value exchange takes place between them?

“And that’s where I come in — your guardian angel. I offer them a cut to keep the house going. After that, they don’t care what I do, as long as the money arrives every year.”

On the surface, the exchange appears straightforward: Mickey pays them, they provide land and silence. For his business, this enables production and infrastructure to operate with minimal risk. But beyond this, they provide a far more valuable asset — social legitimacy. The ability to circulate within high society not as an exotic outsider, but as “one of the group”. Access to a closed social circuit that cannot be purchased directly with money.

In return, Mickey offers more than financial support for maintaining estates. He solves problems — not formal ones, but real, personal, reputational and toxic ones. The storyline involving one lord’s drug-addicted daughter is simply the most visible example. What matters is not intervention itself, but Mickey’s role as a point of support — someone capable of dealing with issues that cannot be discussed publicly.

What opportunities and risks does this partnership structure create?

This is where an often-overlooked aspect of partnerships emerges: they are not only sources of opportunity, but also of constraint and risk. Public exposure can attract unwanted attention — as shown in the film when the publisher’s retaliation for Mickey’s support of a lord leads to one of Mickey’s hidden sites being exposed.

Moreover, the aristocratic lifestyle brings its own risks: inherited trauma, excess, and a sense of impunity. Mickey expects infrastructure and silence; instead, he finds himself managing crises far deeper and messier than initially anticipated.

How does Mickey manage his key partners? And what gives him influence over them?

“Getting yourself a lord is a good thing — but it’s not easy. Takes work. Wine. Women. Disco.”

Money is the baseline. But the real currency is involvement and a sense of security. Mickey builds relationships not through contracts, but through ongoing support, engagement and a willingness to assume responsibility where his partners cannot. Beyond “wine, women and disco”, he solves problems.

Translated into business language, the conclusion is clear. Key partners are not those who help you build a product, marketing or sales. They are independent actors whose resource exchange allows your business model to function — and, at times, enables you to achieve personal objectives as well.

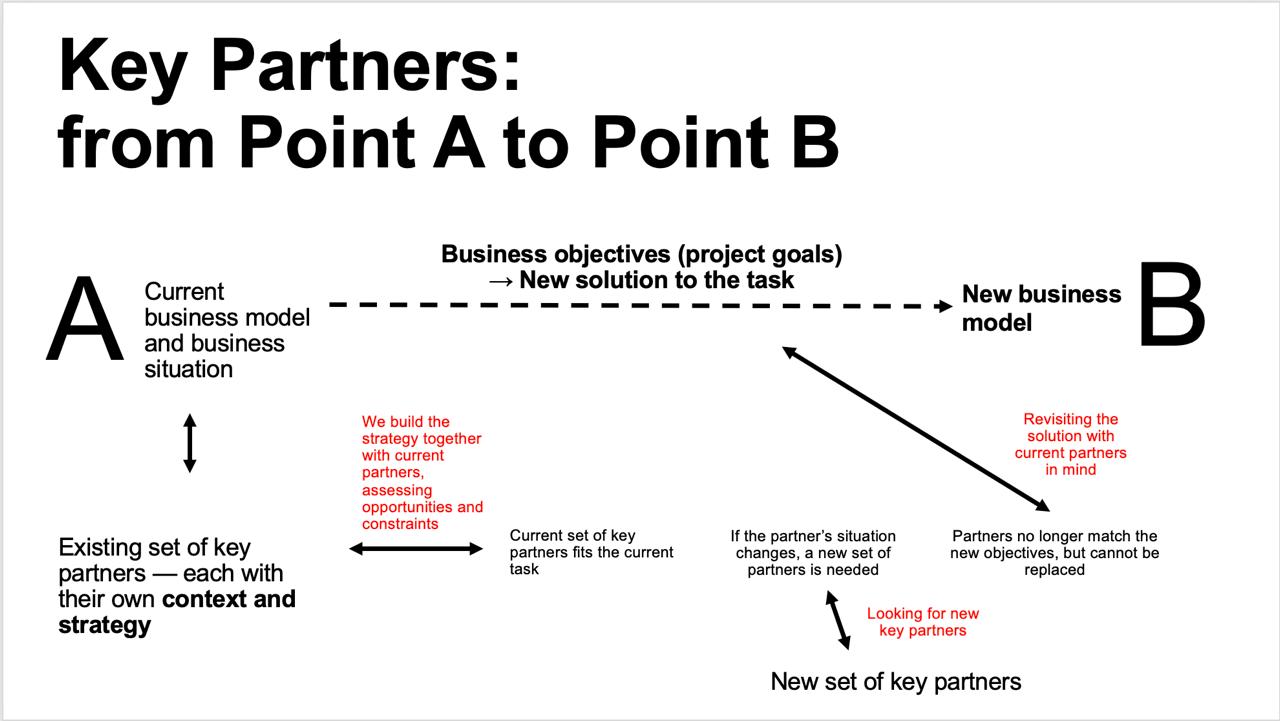

In this sense, partnerships do not simply “emerge”. They are deliberately designed.

This is precisely what the course Key Partners as an Element of Business Strategy is about. Because in real business, things work in much the same way — just without Guy Ritchie’s stylistic flair.